Leafcutter Ants, the best known species of which is Atta cephalotes, are among the most fascinating creatures on the planet. Fourmiculture invites you to discover them through this blog which will allow you to develop new knowledge about these unusual ants.

If you wish to buy Atta cephalotes leafcutter ants, check our available stock on the website or contact us.

Presentation of the blog:

This blog consists of presenting the breeding of Leaf Cutter Ants of the Atta cephalotes species. It will be updated regularly with new information on the evolution of our colony, our observations and our discoveries. We start breeding with a queen, a few workers and a symbiotic fungus. This way, you will be able to observe the development of this colony and better understand its needs and its behavior. The breeder is Yvain Samuel, head of Fourmiculture.

The photos belong to Fourmiculture and can be distributed for a non-profit purpose against a link to this page.

Presentation of the species:

Leaf Cutter Ants include several species common in South America and the southern United States. The best known are Atta cephalotes and Acromyrmex octospinosus. They are commonly called “Leaf Cutters”, but also “Mushroomers”, “Defoliators” or even “Parasol”. The reason being that they leave the anthill in large numbers to cut and collect various plants, including leaves in particular, which they carry above their heads until bringing them back to the nest.

(the following photo is copyright free)

However, ants are unable to feed on leaves directly. They live in symbiosis with a fungus, often called by the Latin term “fungus”. It is in fact a kind of mycelium (underground and stringy part of mushrooms). It is on this mushroom that the ants place the plants and it will feed on it and develop. Very quickly, the fungus will develop edible (gongylidia) by the ants. It thus represents the almost exclusive food of Atta and Acromyrmex ants, simply supplemented by the sap of the plants that they cut up. The larvae are also fed on these growths of the fungus.

The smallest workers, who we like to call “gardeners”, specialize in mushroom care. They prune it, protect it from other fungi and infections using antibiotics produced by their bodies and re-seed the fungus using their droppings.

It is a very advanced symbiosis. Ants are unable to live without the fungus because it is their tool to digest their food externally. And the fungus cannot live more than a few days without the ants.

This very advanced micro-agriculture was invented long before humans, around 60 million years ago by ants.

The growth of the fungus depends on the supply of food and the number of workers to care for it. The fungus can therefore regulate the growth of the colony, but it is rather the opposite that occurs: a small colony is only able to take care of a small mycelium and the queen regulates the laying so that the population n does not increase too quickly in relation to the amount of food available.

Raising Leafcutter Ants:

Atta cephalotes and Acromyrmex octospinosus do not breed in conventional artificial anthills. They need a lot of free space to allow the fungus to grow. This space must be closed but allow oxygen to enter and allow the CO² produced by the fungus to be evacuated. The humidity must also be high.

However, the mycelium fears the slightest draft and excess humidity such as condensation and direct contact with water.

Since these conditions are sometimes opposed, it can be difficult to bring them together. Luckily, once that's done, keeping leafcutter ants is pretty straightforward.

Then, any feeding area connected to the main enclosed space allows food to be deposited and waste to be evacuated. There are no special conditions for this part of the nest but it may be wise to offer them an additional closed space for waste separated from the open space for food.

First part of the blog: Installation of ants

July 5, 2012:

I received the ants from an experienced breeder. Originally, this colony of leafcutter ants comes from South America. They arrived in 48 hours in a simple plastic box with the colony, the mushroom and pieces of leaves.

Here is the planned setup:

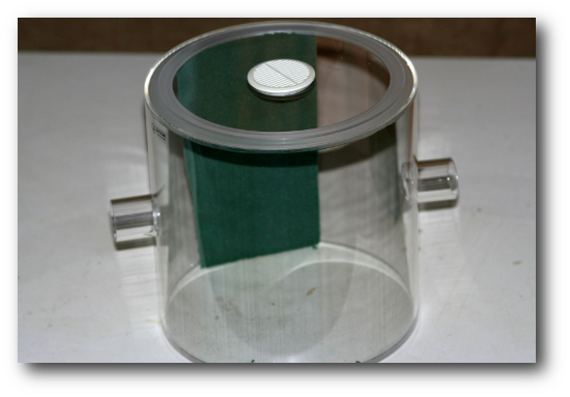

– 1 large 20x20cm Plexiglas cylinder with 1 lid, ventilated and 2 holes

– Ventilation should not be too important in order to maintain good humidity. One of the holes is plugged and the top ventilation is covered with cotton. This is a good technique for gently ventilating the interior of the anthill.

– The bottom of the nest is covered with moist clay balls to maintain the humidity that the ants need.

– A round plastic box (Petri dish) contains the colony and allows it to live in humidity without touching the ground which could be too wet.

– A pipe allows the ants to leave the nest and go to the feeding area, a large container that will be used to deposit the leaves and evacuate the waste. The walls are covered with Venetian talc to prevent ants from climbing.

Only, the fungus is in pieces and covered with bits of leaves. It really does not seem to be in good condition… Here is the colony placed in its Petri dish, itself placed in the cylinder:

Observing the colony, one thing is completely amazing: the size of the queen… She is one of the biggest ants in the world, and it is only by seeing her that you realize how big she is. is impressive! It measures approximately 3cm!

The Atta cephalotes therefore have incredible size differences between workers ranging from 3 to 20mm approximately and a queen of 30mm...

Acromyrmex have a much smaller queen (about 12mm) and the largest workers do not exceed the size of the queen.

Here is the queen, head down in the image, with a little worker on her back!

And here, a fairly large worker, with a very massive head housing powerful muscles for cutting leaves into small pieces. We see that there is brood (the white things). And the fungus always appears scattered.

To circulate easily, not to slip in the glass tube which connects the nest to the harvesting area, and to descend easily along the wall, a cotton wick for candles has been placed.

The queen takes the opportunity to go climbing!

July 10, 2012:

Let's start with some interesting photos. Here is first the mushroom with the queen in the background and already good size workers are present.

We can already observe the fascinating behavior of leafcutter ants during harvesting... All you have to do is deposit plants for workers of all sizes, except for small planters, to take charge of cutting up leaf plots which will be brought back to the nest.

The leaves are brought back to the nest through the glass tube that leads to the nest:

Once inside, increasingly smaller workers cut the leaf into tiny pieces to place on the mushroom.

Unfortunately, mold has appeared under the petri dish in which the colony is placed. The humidity between the box and the clay balls is the cause and the nest must remain as healthy as possible so that the ants can live.

The colony was therefore moved into a new Plexiglas cylinder and the clay balls were replaced by pearlite. The petri dish was pierced with a hot needle to allow air to circulate and the dish was raised so as not to touch the moist substrate.

It's a good start, but already, the ants are depositing waste on the perlite and it's worrying for the future...

January 2, 2013

Other molds and mites harmful to the colony appeared. The ants tended to leave waste on the perlite and the humidity ended up making the nest unhealthy. The conclusion was simple: no substrate should be used. The ants were moved again and installed in an empty, clean cylinder. A damp Oasis foam wall provides the necessary humidity.

It is surprising to see that in a clean nest, without substrate, the ants systematically evacuate the waste from the nest whereas with substrate, the ants tended to deposit it on it, creating mould!

The growth of the fungus resumed the next day and the activity of the ants is greatly accelerated! Proof that this change was necessary.

Here is the ant colony a few days later.

The hole on the right has been filled with oasis moss. Ants can therefore dig it if they need more air and less humidity. However, on the contrary, they seem to want to block this area even more, a sign of a significant need for humidity. The foam is therefore regularly moistened in turn.

End of the experiment:

The colony successfully grew until almost half the nest was filled with its mycelium. Births have been regularly observed with increasingly large soldiers. The colony was eventually sold to female biology students at Versailles.